A bikini-clad teenage girl is thrown face down on the ground while crying out for her mother. A man is shot in the back several times while fleeing a routine traffic stop. Another teenager is killed near Ferguson, Missouri. Police gun down an Ohio man carrying a toy. A woman calls 911 while Indiana police bust the window of her car. A North Carolina teen is mistaken for an intruder and pepper-sprayed in his own home.

Each new incident piles on yet another layer on to the police-versus-the-black-community narrative that has created a deadly fight-versus-flight syndrome—a “choice” that killed unarmed Mike Brown, Sean Bell, John Crawford Jr. and makes black men 21 times more likely to die at the hands of police.

Fight—or flight. But are these really the only two choices?

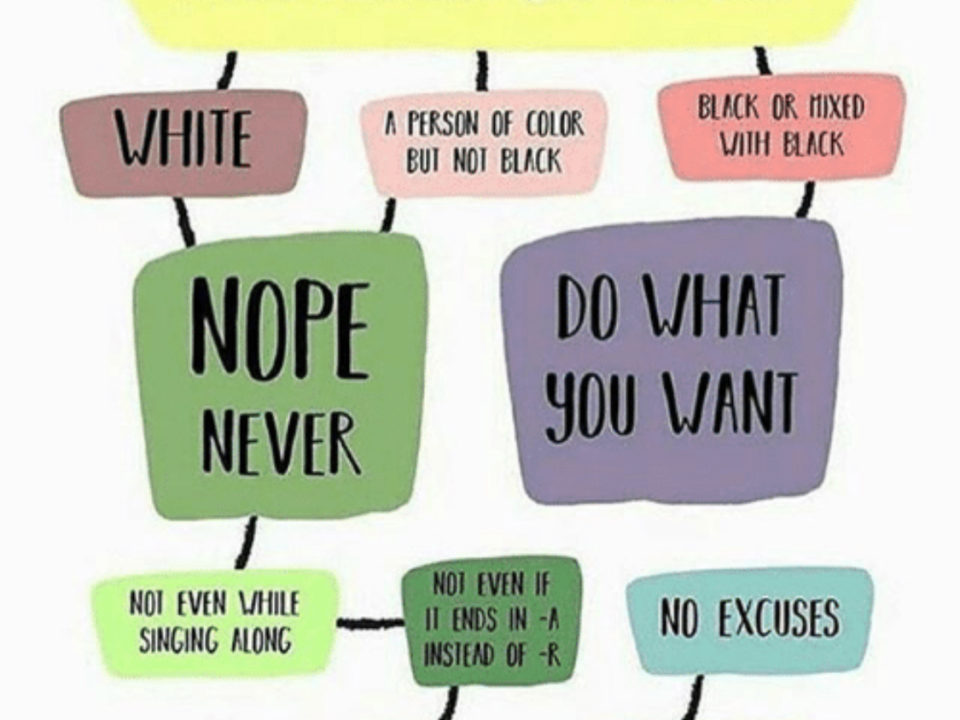

I am a black woman, wife of a black man, mother of two black boys. I’m also a psychiatrist that trains police officers to deescalate potentially deadly interactions involving individuals with mental illness – another group that is commonly feared and stigmatized. In order to forge a new narrative between police and black males, every American-- civilian and law enforcement alike—must accept that biologically speaking, every last bone in your body is prejudiced.

The sooner we can get out of denial about that, the sooner we can begin doing something about it.

Prejudice is defined as a preconceived idea. If someone handed you a big, shiny, red apple, you could describe exactly what it would taste like. Except, you can’t. You can describe what the big, shiny, red apple you ate yesterday tastes like – but in reality, you have no idea what the apple in your hand tastes like, because you’ve not yet taken a bite. Although we place significantly more value judgment on our preconceived ideas about people, the brain-based processes are exactly the same. Have you ever met someone for the first time and liked them before you knew them? Conversely, have you ever developed a fear response to a stranger that could only be based on past experiences as you’ve never met that person?

Throughout our lives, our brains are constantly logging new information and using it to form thoughts, opinions and preconceived notions. Estimated at around 70,000 per day, those thoughts are shaped by a part of the brain called the limbic system—a system that is dedicated to self-preservation and seeks to protect us by generating conditioned responses to environmental stimuli. In plain English, based on previous experiences, the limbic system, often without our voluntary input, senses perceived danger, generates a fear stimulus and commands the thinking part of the brain (known as the prefrontal cortex) to execute a plan for self-preservation. The prefrontal cortex then has to decide what the behavioral response will be. Unfortunately, a prefrontal cortex that has not been trained to challenge the information brought forward by the limbic system, can only take that information for absolute truth, and will react immediately, almost reflexively to neutralize the danger.

Fortunately, Crisis Intervention Team (C.I.T.) training, started in 1988, proves that the prefrontal cortex of law enforcement officers can be trained to resist inaccurate limbic system information. The C.I.T. program which trains law enforcement on how to more safely respond to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis, has demonstrated reduced officer stigma and prejudice, reduced injuries, reduced involvement of SWAT teams and reduced police shootings of individuals with mental illness.

To be sure, some will read this piece and immediately develop a visceral response to the title alone. Unable to stomach that idea that they share anything in common with the officers involved in the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice and Walter Scott, the limbic system may command the prefrontal cortex to run, thereby thwarting the opportunity for honest dialog.

Others will argue that officers must be held accountable for their behaviors. Absolutely. Consequences are known to be a main driver of behavioral change. However, consequences change behaviors after they have already occurred. I think we can all agree that we are seeking to change this behavior before another black teen is shot and killed by another police officer.

On a simple level, I am advocating for racial bias training, modeled after the C.I.T. program, to be added to police officer training for all departments in this country. On a more complex level, I am challenging every person in this country to give up the dream of a prejudice-free society. We are all human. As a result, entirely by fault of our limbic systems, we are all prejudiced. Today, let’s take the first step towards creating a dialog that would allow an Officer Wilson to say “I killed Mike Brown because I was afraid of him. I was afraid of him at least in part because of prejudices I have formed throughout my life. In that moment, my fear led my prefrontal cortex to believe I had no other choice but to kill him. In hindsight, I wish I had made a different decision.”

I am not putting words in Officer Wilson’s mouth, but is it not possible that in the seven seconds it took to kill Mike Brown, this was his experience? And would it not help us move forward as a country, for him to be able to say that; and for us to be able to hear that; and for there to be a mandatory program to strengthen the prefrontal cortices of officers around this country before they ever hit the streets so that just maybe, in the less than ten seconds within which they have to make life and death decisions, they might be able to choose life despite the fear response that tries convince them that death is the only option?

Dr. Nzinga Harrison is an Atlanta-based physician with specialties in Psychiatry and Addiction Medicine and co-founder of Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform, an organization that seeks to eliminate the negative health consequences of interactions with the criminal justice system.